Why a Makino isn’t enough

Stop competing on price! Learn how to combat commoditization — exemplified by the Makino’s effect on the manufacturing industry.

Pop Quiz: You’ve just been signed up for a bicycle race, and you’re given the option of two different tires. You need to select the one that will get you across the finish line faster. Which do you choose?

You probably selected the narrower tire, right? It makes sense; big = cumbersome, and cumbersome = slow. The technical aspects of bicycles have been well-established among cyclists for almost a century: if you want to go fast, you choose narrow tires.

But what if I told you that this isn’t true? That a century of professionals and hobbyists were, in fact, wrong?

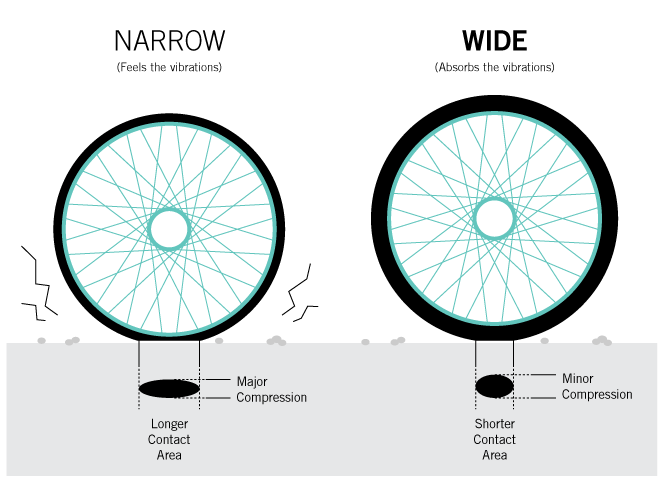

Recent studies have found that the narrow-is-better notion was largely a placebo effect: narrow tires feel faster because they vibrate more, and until recently there was little reason to question whether they actually were faster. When that assumption was finally challenged, a century-old misconception was debunked: It turned out that wider tires are faster due to their shorter contact area, which deforms less as they roll.

If you’re not a cyclist, you may not find this news very jarring… but bicycle tires are hardly the only victim of this phenomenon. The world is filled with preconceived notions – many of which are incorrect, but so entrenched in our collective psyche that we’ve never questioned them.

Just to name a few: Bats are not blind – all bat species have eyes and are capable of sight. Napoleon Bonaparte was not short – he stood 5’7”, which was actually slightly taller than the average Frenchmen of his day. Waiting an hour after a meal before swimming does nothing to reduce risk of cramps or drowning. There is no such thing as a “sugar rush,” and sugar does not cause hyperactivity in children. A penny dropped from the top of the Empire State Building would not kill anyone or crack the sidewalk (although they still don’t recommend it).

And yet, we still use expressions like “blind as a bat” or refer to someone as having a “Napoleon complex” regularly, and in all likelihood this summer parents will still be telling their children to let their hot dogs digest before jumping in the pool.

And of course, business maxims are not immune either. I can scarcely think of worse advice than “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Grammar aside, with this attitude we wouldn’t have cars, or iPhones, or Netflix. Why? Because horses, landlines, and Blockbusters weren’t broken. And yet, this adage permeates our business vernacular.

Recently on the Kinesis blog, we talked about how the name of the game in marketing has long been “frequency” – get in front of your customers as often as possible, and inundate them with your message in the hopes that they may one day pick up the phone. We, too, supported this long-established philosophy – until (like bicycle manufacturers) we sat down and asked ourselves whether this approach was actually proving effective.

The risk of these types of preconceived notions are even more pronounced in our world today. We are constantly faced with a barrage of misinformation, often contradicting itself.

Google Dublin Open Office // Photo by Peter Wurmli/Camenzind Evolution

Take the open office concept, for example. The history of the collective open office began with architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright calling cubicles “fascist and totalitarian.” So, enter the open office: the modern, flexible configuration encouraged transparency and employee collaboration, hailed by companies like WeWork – saying “Basically we are going back to the way it was before the cubicle was created.” But it wasn’t long before critics began pointing out drawbacks – claiming that they were actually a hindrance to productivity and teamwork.

CubeSpace Closed Office // Photo by Asa Wilson on Flickr

This is exquisitely illustrated in the evolution of how FastCompany handled this discourse: even across a single publication, they have an article about how the open office trend is reversing itself, then another claiming to be the “final nail in the coffin” for open plan office spaces, then another allowing that while the open office plan sucks, it may still be good for you… and finally, an architect’s defense of why open offices are still effective. To underscore this duality, they even feature the pros and cons of open layouts in a written debate between two of their editors.

So, as a business leader planning your office layout, how can you even begin to make an educated decision?

Unfortunately, some industries are capitalizing on this state of affairs, and on our tendency to take things at face value. They are tapping into our primitive emotional responses to entice us to buy from them, think a certain way, or take action. So, it is more important than ever to learn how to stay informed and make educated choices. Here are some tips:

We live in an age of clickbait headlines, “listicles,” and other easy-to-digest content. While convenient, these spoon-fed conclusions hamper our ability to think critically and ask the tough questions about the trustworthiness of the content we’re consuming.

Whoever is giving you a piece of advice (be it a friend, consultant, or magazine article), ask yourself what they stand to gain if you heed it. If a study is released showing that open workplaces should be avoided at all costs, check to make sure the study wasn’t funded by a cubicle manufacturer.

This goes for content you receive from us, too! We are in the business of giving advice – but we encourage healthy skepticism. (For example, what might we have to gain by writing this article? Perhaps a readership that scrutinizes information, so that we as a potential partner may hold up to that scrutiny?)

Many of the open office studies were performed at Fortune 500 companies – which means the advice they doled out, pro or con, was likely irrelevant to many of their readers anyway. There may be cyclists who still prefer a narrow tire for reasons entirely unrelated to speed – the same way that parents may still have children wait before swimming simply because they want a short break before playing lifeguard. Consider the variables affecting your decision-making, and what is really important to you.

Many of the decisions we make on a daily basis are driven by urgency, and by extension, emotion. When we don’t have the time to devote to an important choice, we default to the option that is easiest – which is why we often bend to the persuasive salesperson peddling a product we don’t need, or hire the charismatic employee rather than the qualified one.

"Like riding a bike" is an adage that has been used to refer to something you can learn once and know forever. But as we've seen, even with bicycles, this confidence of information can be a hindrance to clear decision-making, particularly in business.

So ask yourself: What are the long-held beliefs currently powering your decision-making process, and how can you revisit them to shift your perspective?

Get insights like this straight to your inbox.